The concept of homecoming has special meaning for Gina Gongora, who, along with her partner Fernando Gomez Vivas, co-founded Vagantes—a collection of eight homes as well as its own agency specializing in management, design, and architecture. Located in Mexico’s Yucatan and based out of its cultural epicenter of Merida, these homes invite travelers with a distinctly slow-paced, unhurried charm that transforms them into sanctuaries for local design and escapism.

Founded in 2021, Vagantes is the result of accumulated artistic and travel expertise within a familiar environment. Gina, a multi-generational Yucatan native, takes great pride in highlighting her heritage, its rich design history, and culture through Vagantes. "What you experience here is like true glory," says Gina. But it was their first joint project, Casa Vagantes Montejo, constrained by a personal budget, that birthed a distinctive style that today serves as the common thread among all their subsequent properties.

Gongora’s background does not lie in hospitality but is firmly rooted in aesthetics. After completing her studies in digital design locally, Gongora pursued a fashion course in London. She then embarked on a two-year stint in the digital department at Vogue Mexico in Mexico City. It was during a brief visit to her hometown that she encountered the founders of Coqui Coqui boutique hotels. This sparked a five-year collaboration, during which she returned home and immersed herself in various tasks, from digital media to design and staging. In the meanwhile, Gina nurtured her passion for set design and explored the region's unique landscapes. Gina was already observing the changes in travel patterns and hospitality.

Her path then converged with Fernando, a local architect, and they pooled their skills and passions together. Amidst their local weekend travels, the idea for their collaborative venture began to take shape. Initially, drawing on her journalistic background (while continuing to work as a freelance for Vogue Mexico), Gina envisioned the project to be a blog or some sort of written narrative about exploring the Yucatan. And so, “the name [Vagantes] comes from that," Gina reflects, "from being vagabonds and wanderers, from our insatiable curiosity as discoverers. It's a bit chaotic without a fixed structure, but it's about rediscovering on a whim.”

Together with Fernando, they initially purchased Casa Montejo as their personal residence, only to be so happy with the result that they began renting it. And so, Vagantes was born, emphasizing design prowess over literary pursuits.

Despite facing an initial setback with their venture, which operated for only three months before the pandemic struck, they managed to complete two more projects in their first year thanks to the unique aesthetic proposition. Fernando focused on the architectural and structural aspects of the spaces, while Gina delved into interior design, drawing upon her experience from photo shoots, sets, and staging. When outside clients began to approach Gina about interior design, although not her specialty, she felt confident she could make it work.

“All of our interventions are about letting the houses tell us what to do — not to knock down walls or roofs, but rather to really lean into the spaces that the homes give us,” explains Gina. “Reveal and restore what's behind the walls instead of putting on new paint. In a way, it's reliving a little bit of what it was like to live in centro when our grandparents lived there; it was like super slow living — going to the market and meeting people in the neighborhood. It's still possible.” For instance, this approach led them to uncover the stunning green walls of Casa Montejo, which are now one of the distinguishing elements of their style.

Most of the Vagantes homes, including Casa Montejo, Casa San Sebastian, and Casita Vagantes, date back to the early 1900s — with the colonial-style Casa Ermita being the exception. Gongora brought in mid-century furniture to harmonize with a diverse architectural backdrop, resulting in a cohesive aesthetic born out of attention to detail and thoughtful construction methods. They also took a dive into the history and construction methods specific to Yucatan, uncovering walls crafted by stacking rocks and pebbles without mortar, as well as the use of chukum, a tree resin that creates a washed-out effect and provides natural cooling in the relentless summer heat.

Casa Ermita. Photos by Manolo R. Solis @manolorsolis_fotografia

Inside, the Vagantes properties seamlessly integrate the comforts of home with the styles of the region. Encouraging guests to embrace the essence of local living, their spaces loosely echo the layout of a traditional choza Yucateca-style, including a space to sleep, eat, and simply be. Adorned with luxurious four-poster beds, antique furnishings, artisanal artworks, and locally sourced utilitarian objects, they have now gathered a cult following of conscious travelers.

“We like recycling and giving the houses a new life that makes you feel like you are at home,” elaborates Gongora. “Our aim is for guests to feel utterly at ease, where the accidental spill of coffee doesn't cause concern. It's about instilling a sense of value in every aspect of the space yet also embracing its transient nature. Everything within these walls is meant to be utilized and enjoyed; even if something breaks, it's inconsequential in the grand scheme of things. But what’s important are the little things. We have books you can read, bicycles, hats and bags so that you can take them to the market. My grandfather does this every day and I love to see guests participating in these little things of Yucatecan life.” Guests are greeted with henequen bags, hand-weaved hammocks and more upon their arrival.

As the duo expanded their offerings and established a more structured approach, requests for interior design and architectural services began pouring in from external clients. Their management and design portfolio now boasts eight properties, including their latest addition: Casita Vagantes, a charming mini-house complete with a plunge pool. They've ventured into diverse projects alongside their properties, from crafting a speakeasy at Izamal's Restaurant Kanché to designing their own interior design boutique in Merida’s centro. (They also own a two-bedroom property in the town of Izamal as well, one of their farthest properties from Merida.)

Seeing the rise in group travel across Mexico, they designed their first villa, Casa Kantoyna, 20 minutes outside of the city. Tucked amidst tropical gardens, this pink hacienda-like estate accommodates up to eight guests in luxurious seclusion, complete with a private pool.

With expansion on the horizon, they approach it with a humble spirit. “We have put on the robe of ambassadors of Yucatán,” declares Gina in her Yucatecan accent.

Their focus remains on deepening their research, exploring new territories for inspiration, and gradually and thoughtfully expanding their footprint. Despite interest from clients and locales from across Mexico, they remain committed to their grassroots, startup-like approach, eagerly anticipating what the future holds. "To me, Yucatán is like my anchor. Here, you can feel the energy pulsating through the streets, drawing people in with its rich history and captivating charm," Gina explains.

The Yucatan Peninsula has been steadily unveiling its marvels, captivating with its unique rhythm and the warm hospitality of its locals. Merida's surroundings are a treasure trove, boasting ancient Mayan ruins, historic landmarks, cenotes, untouched beaches, and lush jungles. But for Gongora, it's a return to her roots, driven by familial ties and cherished memories of childhood adventures. She fondly recalls navigating streets devoid of names, where family businesses once thrived—a legacy she proudly continues today with Vagantes.

Concrete Poetry

The language of simplicity in Mexico’s new brutalism

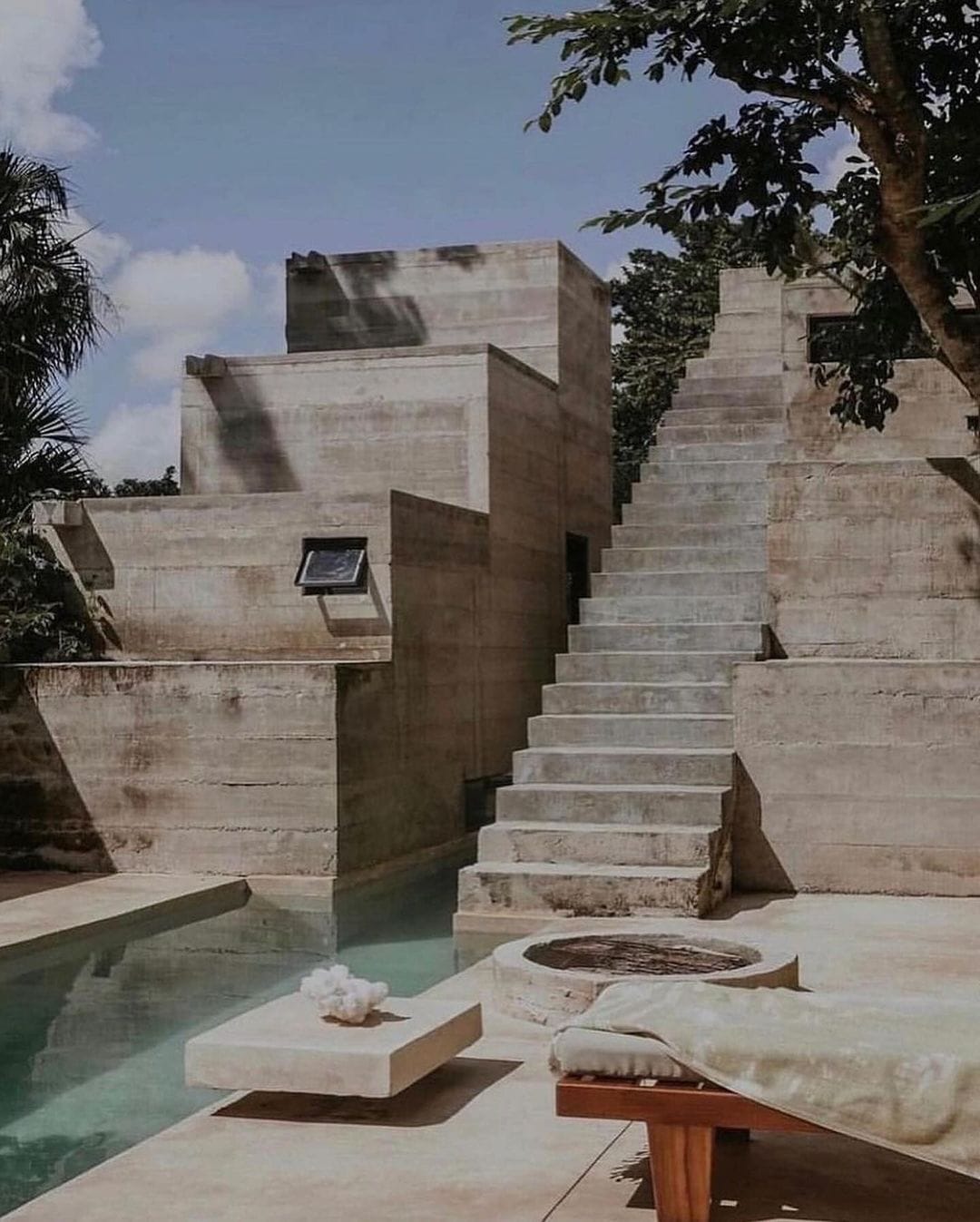

Brutalism is one of the most controversial architectural styles of the 20th century. Characterized by raw concrete and graphic lines, the style rose to prominence in the 1950s and 60s when authorities on both sides of the Iron Curtain sought to convey security, reliability, and awe through architecture. Today, far from the steely skies of post-war Europe, brutalism is making a comeback in a somewhat unexpected context: weekend homes in Mexico.

In their heyday, brutalist buildings were praised for their “ruthless logic” and “bloody-mindedness” by British critic Peter Reyner Banham. Notable examples from the period include Vienna’s Wotruba Church, Boston City Hall, and the UFO-like Monument House of the Bulgarian Communist Party. However, it is these very characteristics that have traditionally drawn ire from the public. Clearly, such adjectives are connected to the popular understanding of the word ‘brutal’ – savage, hard, uncomfortable, punishing.

These are hardly terms that feel suitable for an inviting place to relax, reflect, or feel at home. Yet, Mexican architects are re-purposing the style. By taking its simple, raw practicality, they are re-writing the language of brutalism to create a different kind of poetry in concrete: one that’s elegant, durable, and dramatic.

Rough poetry

The term ‘brutalism’ derives not from English but from French. Bréton brut, meaning raw concrete, was popularized by legendary Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier, who sought to take a practical approach to architecture in the face of post-war austerity: simplistic, honest, and faithful to its raw materials. In his proto-brutalist works such as the Chandigarh Capitol Complex in India (1951-1961), Le Corbusier used raw concrete to incredible effect. For instance, the complex’s Tower of Shadows serves as an exploration of the angles of the sun, utilizing sun breakers or brise-soleil to regulate its rays.

Although Le Corbusier was brutalism’s forebearer, its parents are undoubtedly English architects Alison and Peter Smithson. Working in the UK in the 50s and 60s, the duo were responsible for architectural masterworks (or disasters, depending on what side of the debate you fall on) such as the Hunstanton School and the particularly controversial Robin Hood Gardens estate. Completed in 1972, the social housing complex was spread across broad aerial walkways in long concrete blocks, which the Smithsons affectionately called “streets in the sky”.

Referencing the post-war reality, Alison Smithson stated that their architecture aimed to “drag a rough poetry out of the confused and powerful forces which are at work.” Certainly, many more architects of the period shared their taste for rough poetry: take Denys Lasdun’s National Theatre, which King Charles described as “a clever way of building a nuclear power station in the middle of London without anyone objecting”.

In response to King Charles' comments, the Chair of the Royal British Institute of Architects said that the then-prince was “having an enormous influence on the public perception of architecture, but not on its understanding”. Since, the style fell harshly out of fashion. The National Theatre was dubbed one of Britain’s ugliest buildings; and despite protests from architects including Richard Rogers and Zaha Hadid, demolition of Robin Hood Gardens began in 2017.

But, now, new life is being breathed into brutalism here in Mexico. To paraphrase Alison Smithson, rough poetry in the face of powerful forces is what makes brutalism so relevant to the landscape. By harnessing concrete's durable and pliable nature, architects are manipulating light and space to work in harmony with the natural environment.

Living forces

One of Mexico’s most prominent and prolific neo-brutalist architects is French-born, Mexico City-based Ludwig Godefroy. Like the Smithsons, his design is influenced by the austere realities of post-war Europe; when asked about his principal inspirations, he references the abandoned World War II bunkers that dot the coastline near his sleepy French hometown. These structures, now almost blended into the jagged Atlantic cliffs, hark back to the “confused and powerful forces” of post-war modernity to which Alison Smithson referred.

On his arrival in Mexico in 2006, Ludwig found the same haunting, derelict majesty walking among the pyramids at Teotihuacan. Peter Reyner Banham’s comments on the Smithsons’ work could also be applied to the raw presence of these sacred structures: “[architecture that] eludes precise description while remaining a living force.” Such high-drama influences are evident in Ludwig’s work; take the fortress-like Casa Alferez in La Marquesa, outside Mexico City. Here, Ludwig manipulates monolithic shapes and materials to create a home with an almost ecclesiastical tranquility.

Casa Alferez, La Marquesa, Estado de México, Mexico. Ludwig Godefroy, 2022. Photos by CasitaMX.

However, what struck Ludwig the most about Teotihuacan was the “external interiority” of the Avenue of the Dead. For Ludwig, the atmosphere created by its towering sides and distinctive geometry created a striking marriage between architecture and its context, at once decisive in its presence and harmonious with its surroundings. This particular harmony – or as he puts it, concordancia, a Spanish term usually used in the study of linguistics – is what Ludwig aspires to in his architecture.

Such interaction between the inside and out is facilitated by the buildings’ environment. Whereas Northern European architecture requires shelter from cold winters and wet springs, the warm climates of coastal Mexico allow for more creative interactions with the outdoors. For example, homes like Casa Dzul incorporate pre-hispanic geometry in their corridors and light shafts to create elegant interplays between light, space, and greenery. Ludwig calls them “gardens with houses, rather than houses with gardens.”

Casa Dzul, Merida, Yucatan, Mexico. Ludwig Godefroy, 2023. Photos by Jasson Rodriguez @diafragmas.

Creating refuge

Another acclaimed neo-brutalist property with decidedly poetic inspirations is Mexican architect Aranza de Ariño’s Casa Tiny in Puerto Escondido, Oaxaca. This petite retreat for two features pared-back geometry with elegant amenities, creating the perfect balance between off-the-grid escapism and chic interior design. Described by the architect as “A Walden for two”, the home’s design is a homage to Henry David Thoreau’s treatise on the virtues of solitude, contemplation, and closeness to nature.

The home’s modest scale and stripped-back materials demand that you take a moment, step back, and reflect. Although Casa Tiny’s robust concrete walls are a far cry from the rickety shack described in Thoreau’s Walden, the rawness of the material invites the encroaching jungle and sea air. Like Ludwig Godefroy’s designs, the home at once punctuates and incorporates into the landscape, creating a poetic interplay between the inside and out.

Aranza de Ariño’s Casa Tiny in Puerto Escondido. Photos by Camila Cossio.

Yet the choice of concrete acknowledges that this pleasant climate is also a powerful force. Like the tezontle of the pyramids, the bunkers of Ludwig’s childhood, and indeed much of the cast concrete used in Mexico’s rural architecture, these structures’ solid walls will persist in the face of heat, hurricanes, and seismic events, at once perfectly integrated and sharply separate from their environment.

Building With Intention

Espacio 18 is an architectural practice that also seeks to create buildings that are at once sanctuaries and eulogies to their environment. In an interview with their founding partner Mario Ávila, he explained that rather than being wedded to a specific style, Espacio 18 seeks to tailor every project to its context. He referenced the words of revered Catalan architect Enric Miralles: “I want my architecture to be invisible.”

Casa del Sapo, also situated on the Oaxacan coast, is far from invisible. Indeed, its dramatic concrete walls make it a spectacular landmark on the rugged cliffs. But, in spite of its contrast with its surroundings, Casa del Sapo pays tribute to its environment. For Espacio 18, there is no decision without pure intention: the 130-square-meter house is configured across 45-degree angles to take full advantage of the sea and mountain views. This particular configuration also modulates the effect of the climate; the layout mitigates the need for air conditioning, as the structure’s angles create shelter from the sun and facilitate efficient air circulation.

The choice of materials is also a direct response to the context. Casa del Sapo combines clean block concrete with references to its Oaxacan roots, incorporating adobe brickwork and a reed palapa across the connecting terrace. Indeed, the concrete itself is a very deliberate choice; although not classically associated with sustainability (in fact quite the opposite), its use has an important connection to localism. Ultimately, it’s what’s available.

Using concrete allows the architects to work with local craftsmen and construction teams, leveraging local expertise rather than displacing these capable craftsmen with imported teams or materials. Ludwig echoed this sentiment in an interview with CasitaMX: “I always work with the skills and materials that are locally available. This is because true to my style, I always try to strip things back to their simplest form. I consume less to create buildings that last.”

A practical poem

The resurgence of brutalism in Mexican architecture marks a compelling fusion of raw practicality and poetic expression. Departing from its historical associations with monumental government structures and austere urban landscapes, contemporary Mexican architects are reinterpreting brutalism as a language of simplicity and harmony with nature.

Drawing inspiration from pre-Hispanic and European monuments alike, architects like Ludwig Godefroy create homes that resonate with their surroundings while offering sanctuary from the elements. Similarly, projects like Aranza de Ariño's Casa Tiny evoke the spirit of solitude and communion with nature, inviting contemplation through pared-back geometry and simple materials.

Nonetheless, this newfound appreciation for brutalism does not neglect the realities of Mexico's climate and context. Practices like Espacio 18 emphasize the importance of tailoring each project to its environment, utilizing materials like concrete not only for their durability but also for their connection to local craftsmanship.

In Mexico’s new brutalism, the language of simplicity speaks volumes. This approach offers a testament to Mexico's rich architectural heritage while embracing the present day’s social and environmental challenges. Through a synthesis of form and function, Mexican architects are forging a new architectural language that writes concrete poetry across the landscape.