mexican architecture

Concrete Poetry

The language of simplicity in Mexico’s new brutalism

Brutalism is one of the most controversial architectural styles of the 20th century. Characterized by raw concrete and graphic lines, the style rose to prominence in the 1950s and 60s when authorities on both sides of the Iron Curtain sought to convey security, reliability, and awe through architecture. Today, far from the steely skies of post-war Europe, brutalism is making a comeback in a somewhat unexpected context: weekend homes in Mexico.

In their heyday, brutalist buildings were praised for their “ruthless logic” and “bloody-mindedness” by British critic Peter Reyner Banham. Notable examples from the period include Vienna’s Wotruba Church, Boston City Hall, and the UFO-like Monument House of the Bulgarian Communist Party. However, it is these very characteristics that have traditionally drawn ire from the public. Clearly, such adjectives are connected to the popular understanding of the word ‘brutal’ – savage, hard, uncomfortable, punishing.

These are hardly terms that feel suitable for an inviting place to relax, reflect, or feel at home. Yet, Mexican architects are re-purposing the style. By taking its simple, raw practicality, they are re-writing the language of brutalism to create a different kind of poetry in concrete: one that’s elegant, durable, and dramatic.

Rough poetry

The term ‘brutalism’ derives not from English but from French. Bréton brut, meaning raw concrete, was popularized by legendary Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier, who sought to take a practical approach to architecture in the face of post-war austerity: simplistic, honest, and faithful to its raw materials. In his proto-brutalist works such as the Chandigarh Capitol Complex in India (1951-1961), Le Corbusier used raw concrete to incredible effect. For instance, the complex’s Tower of Shadows serves as an exploration of the angles of the sun, utilizing sun breakers or brise-soleil to regulate its rays.

Although Le Corbusier was brutalism’s forebearer, its parents are undoubtedly English architects Alison and Peter Smithson. Working in the UK in the 50s and 60s, the duo were responsible for architectural masterworks (or disasters, depending on what side of the debate you fall on) such as the Hunstanton School and the particularly controversial Robin Hood Gardens estate. Completed in 1972, the social housing complex was spread across broad aerial walkways in long concrete blocks, which the Smithsons affectionately called “streets in the sky”.

Referencing the post-war reality, Alison Smithson stated that their architecture aimed to “drag a rough poetry out of the confused and powerful forces which are at work.” Certainly, many more architects of the period shared their taste for rough poetry: take Denys Lasdun’s National Theatre, which King Charles described as “a clever way of building a nuclear power station in the middle of London without anyone objecting”.

In response to King Charles' comments, the Chair of the Royal British Institute of Architects said that the then-prince was “having an enormous influence on the public perception of architecture, but not on its understanding”. Since, the style fell harshly out of fashion. The National Theatre was dubbed one of Britain’s ugliest buildings; and despite protests from architects including Richard Rogers and Zaha Hadid, demolition of Robin Hood Gardens began in 2017.

But, now, new life is being breathed into brutalism here in Mexico. To paraphrase Alison Smithson, rough poetry in the face of powerful forces is what makes brutalism so relevant to the landscape. By harnessing concrete's durable and pliable nature, architects are manipulating light and space to work in harmony with the natural environment.

Living forces

One of Mexico’s most prominent and prolific neo-brutalist architects is French-born, Mexico City-based Ludwig Godefroy. Like the Smithsons, his design is influenced by the austere realities of post-war Europe; when asked about his principal inspirations, he references the abandoned World War II bunkers that dot the coastline near his sleepy French hometown. These structures, now almost blended into the jagged Atlantic cliffs, hark back to the “confused and powerful forces” of post-war modernity to which Alison Smithson referred.

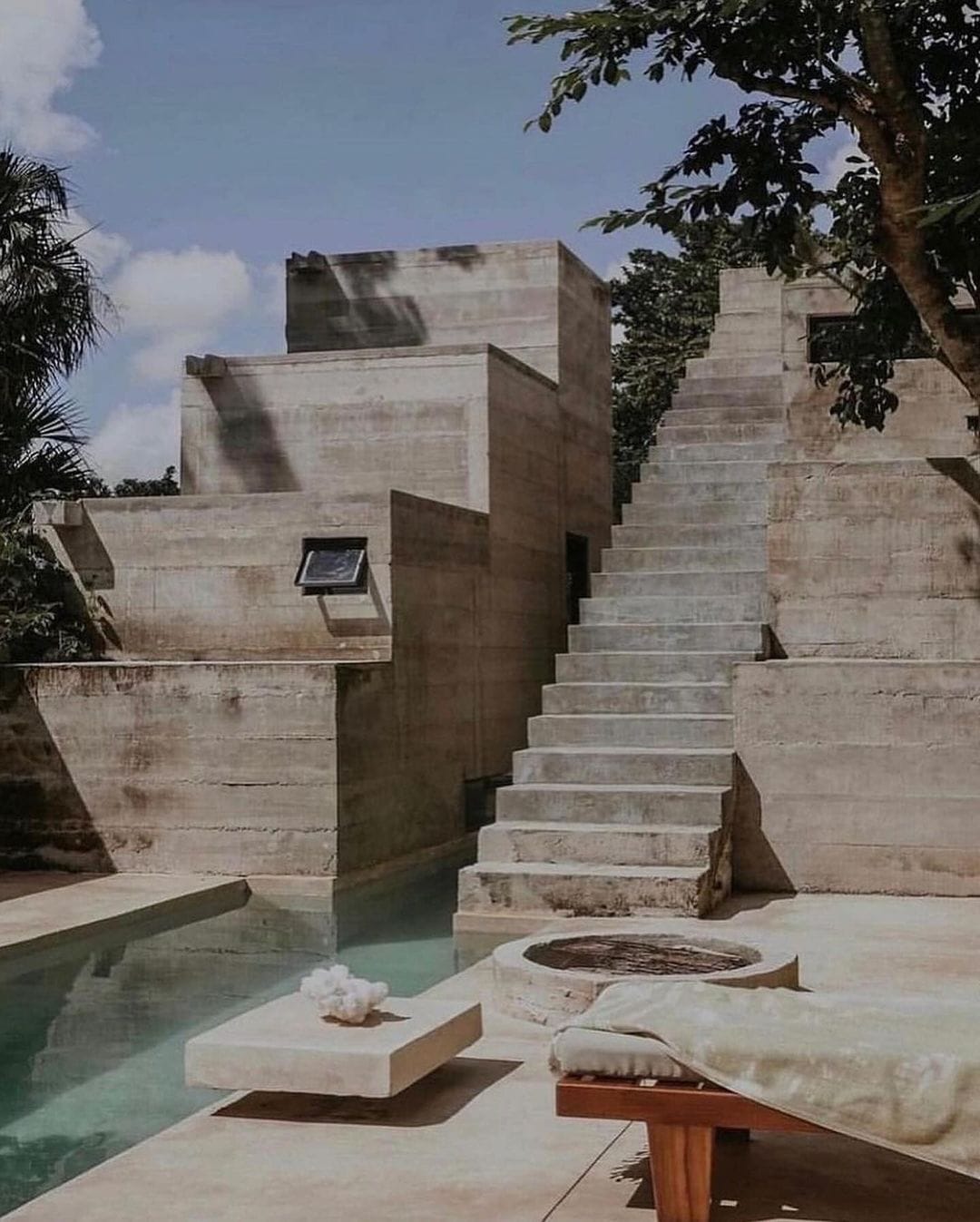

On his arrival in Mexico in 2006, Ludwig found the same haunting, derelict majesty walking among the pyramids at Teotihuacan. Peter Reyner Banham’s comments on the Smithsons’ work could also be applied to the raw presence of these sacred structures: “[architecture that] eludes precise description while remaining a living force.” Such high-drama influences are evident in Ludwig’s work; take the fortress-like Casa Alferez in La Marquesa, outside Mexico City. Here, Ludwig manipulates monolithic shapes and materials to create a home with an almost ecclesiastical tranquility.

Casa Alferez, La Marquesa, Estado de México, Mexico. Ludwig Godefroy, 2022. Photos by CasitaMX.

However, what struck Ludwig the most about Teotihuacan was the “external interiority” of the Avenue of the Dead. For Ludwig, the atmosphere created by its towering sides and distinctive geometry created a striking marriage between architecture and its context, at once decisive in its presence and harmonious with its surroundings. This particular harmony – or as he puts it, concordancia, a Spanish term usually used in the study of linguistics – is what Ludwig aspires to in his architecture.

Such interaction between the inside and out is facilitated by the buildings’ environment. Whereas Northern European architecture requires shelter from cold winters and wet springs, the warm climates of coastal Mexico allow for more creative interactions with the outdoors. For example, homes like Casa Dzul incorporate pre-hispanic geometry in their corridors and light shafts to create elegant interplays between light, space, and greenery. Ludwig calls them “gardens with houses, rather than houses with gardens.”

Casa Dzul, Merida, Yucatan, Mexico. Ludwig Godefroy, 2023. Photos by Jasson Rodriguez @diafragmas.

Creating refuge

Another acclaimed neo-brutalist property with decidedly poetic inspirations is Mexican architect Aranza de Ariño’s Casa Tiny in Puerto Escondido, Oaxaca. This petite retreat for two features pared-back geometry with elegant amenities, creating the perfect balance between off-the-grid escapism and chic interior design. Described by the architect as “A Walden for two”, the home’s design is a homage to Henry David Thoreau’s treatise on the virtues of solitude, contemplation, and closeness to nature.

The home’s modest scale and stripped-back materials demand that you take a moment, step back, and reflect. Although Casa Tiny’s robust concrete walls are a far cry from the rickety shack described in Thoreau’s Walden, the rawness of the material invites the encroaching jungle and sea air. Like Ludwig Godefroy’s designs, the home at once punctuates and incorporates into the landscape, creating a poetic interplay between the inside and out.

Aranza de Ariño’s Casa Tiny in Puerto Escondido. Photos by Camila Cossio.

Yet the choice of concrete acknowledges that this pleasant climate is also a powerful force. Like the tezontle of the pyramids, the bunkers of Ludwig’s childhood, and indeed much of the cast concrete used in Mexico’s rural architecture, these structures’ solid walls will persist in the face of heat, hurricanes, and seismic events, at once perfectly integrated and sharply separate from their environment.

Building With Intention

Espacio 18 is an architectural practice that also seeks to create buildings that are at once sanctuaries and eulogies to their environment. In an interview with their founding partner Mario Ávila, he explained that rather than being wedded to a specific style, Espacio 18 seeks to tailor every project to its context. He referenced the words of revered Catalan architect Enric Miralles: “I want my architecture to be invisible.”

Casa del Sapo, also situated on the Oaxacan coast, is far from invisible. Indeed, its dramatic concrete walls make it a spectacular landmark on the rugged cliffs. But, in spite of its contrast with its surroundings, Casa del Sapo pays tribute to its environment. For Espacio 18, there is no decision without pure intention: the 130-square-meter house is configured across 45-degree angles to take full advantage of the sea and mountain views. This particular configuration also modulates the effect of the climate; the layout mitigates the need for air conditioning, as the structure’s angles create shelter from the sun and facilitate efficient air circulation.

The choice of materials is also a direct response to the context. Casa del Sapo combines clean block concrete with references to its Oaxacan roots, incorporating adobe brickwork and a reed palapa across the connecting terrace. Indeed, the concrete itself is a very deliberate choice; although not classically associated with sustainability (in fact quite the opposite), its use has an important connection to localism. Ultimately, it’s what’s available.

Using concrete allows the architects to work with local craftsmen and construction teams, leveraging local expertise rather than displacing these capable craftsmen with imported teams or materials. Ludwig echoed this sentiment in an interview with CasitaMX: “I always work with the skills and materials that are locally available. This is because true to my style, I always try to strip things back to their simplest form. I consume less to create buildings that last.”

A practical poem

The resurgence of brutalism in Mexican architecture marks a compelling fusion of raw practicality and poetic expression. Departing from its historical associations with monumental government structures and austere urban landscapes, contemporary Mexican architects are reinterpreting brutalism as a language of simplicity and harmony with nature.

Drawing inspiration from pre-Hispanic and European monuments alike, architects like Ludwig Godefroy create homes that resonate with their surroundings while offering sanctuary from the elements. Similarly, projects like Aranza de Ariño's Casa Tiny evoke the spirit of solitude and communion with nature, inviting contemplation through pared-back geometry and simple materials.

Nonetheless, this newfound appreciation for brutalism does not neglect the realities of Mexico's climate and context. Practices like Espacio 18 emphasize the importance of tailoring each project to its environment, utilizing materials like concrete not only for their durability but also for their connection to local craftsmanship.

In Mexico’s new brutalism, the language of simplicity speaks volumes. This approach offers a testament to Mexico's rich architectural heritage while embracing the present day’s social and environmental challenges. Through a synthesis of form and function, Mexican architects are forging a new architectural language that writes concrete poetry across the landscape.